Courage

Ben Dean, Ph.D.

Defining Courage

"The secret of life is this: When you hear the sound of the cannons, walk toward them."~~Marcel France

Courage is a universally admired virtue, and courageous individuals in all cultures have survived across time to become the heroes of subsequent generations. But what is courage, and what is it not?

Philosophers have pondered these questions since antiquity. But psychologists, who had a significantly later start, have focused more on fear than on courage. The literature reflects this imbalance and contributes to the lack of consensus on a simple definition.

Persistence and Fear: Two Components of Courage?

Most philosophers and psychologists agree that courage involves persistence in danger or hardship. However, some argue that courage is synonymous with fearlessness, while others suggest that the presence or the absence of fear has nothing to do with courage.

Psychologist S. J. Rachman (1990) entered this debate with a definition of courage that takes into account three components of fear:

1) the subjective feeling of apprehension

2) the physiological reaction to fear (e.g., increased heart rate)

3) the behavioral response to fear (e.g., an effort to escape the fearful situation).

These components are imperfectly linked, and it is possible to experience one or two without another. The courageous person effects an uncoupling of fear's components by resisting the behavioral response and facing the fearful situation, despite the discomfort produced by subjective and/or physical reactions.

No Fear, No Courage

If a person is fearless, the behavioral component of fear is not at issue, for there is no reason to avoid or escape something that elicits no subjective or physical sensation of fear.

It seems unwarranted, therefore, to suggest that the fearless person is courageous. Such an assertion would make a virtue out of having an unresponsive autonomic nervous system in circumstances fearful to others.

Unless one experiences the sensation of fear, subjectively and/or physically, no courage is required.

As an astute observer of human behavior, Mark Twain, observed, "Courage is resilience to fear, mastery of fear, not absence of fear" (Fitzhenry, 1993, p. 110).

Different Types of Fear, Different Types of Courage

Whatever the circumstances testing courage, fear must be overcome.

The fear that accompanies physical courage relates to bodily injury or death. It is also possible for a fear of shame, opprobrium, or similar humiliations to spur physical courage, producing what is popularly called the "courage born of fear." In warfare, for example, some individuals may display physical courage because they fear cowardice. Or they may accept that they are cowards yet fear being recognized as such by others.

Moral courage, too, may relate to fear of others' adverse opinions. Looking foolish before peers, for example, is a common fear. But moral courage compels or allows an individual to do what he or she believes is right, despite fear of the consequences. (It should be noted that what is "right" is determined by the individual who chooses to take the risk, not by an observer.)

The fear that can summon moral courage takes many forms: fear of job loss, fear of poverty, fear of losing friends, fear of criticism, fear of ostracism, fear of embarrassment, fear of making enemies, fear of losing status, to name but a few potential human fears. In addition one may fear a loss of ethical integrity or even a loss of authenticity if he or she fails to act in accord with conscience (Putman, 1997).

As there are many variations of fear, there are many dimensions to moral courage, ranging from the social courage represented by Rosa Parks and Gandhi to the political courage represented, if infrequently, by elected officials. The opportunities to act with moral courage are numerous, and the fears calling for moral courage are as varied as individuals themselves.

Promoting Courage

Because courage is a universally admired virtue, most would also consider it an attribute to be promoted and fostered. Indeed, if any virtues are to be cultivated within a society, one might reasonably argue that courage should be foremost among them, for courage may be necessary to maintaining and exercising the other virtues. As C. S. Lewis observed, courage is "not simply one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point" (Fitzhenry, 1993, p. 111).

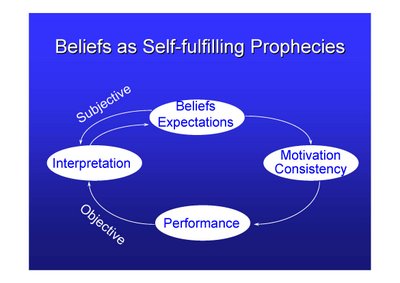

Aristotle believed that an individual develops courage by doing courageous acts (Aristotle, trans. 1962), and there is current support for the suggestion that courage is a moral habit to be developed by practice (Cavanagh & Moberg, 1999). The view is compatible with Bandura's concept of self-efficacy in which successful performances (even vicarious ones) strengthen an expectation of further success (Bandura, 1977). Individuals are more likely to face a situation and attempt to cope with it if their previous experience gives them reason to believe they can meet the challenge.

Building Courage

If you or your clients would like to develop your courage, keep Aristotle in mind this week. Remember his view that we become courageous by being courageous! Design your own courage-building exercises by revisiting a life goal that is gathering dust. Is fear holding you back? How might you break down this goal into smaller steps, with each step requiring a progressively greater amount of courage?

There are no shortcuts, so run toward those cannons!

I hope you enjoyed this newsletter! See you in two weeks when we discuss the character strength Persistence.

Warmly,

Ben Dean

Copyright ©2006, The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All Rights Reserved